Ralph Lowe wasn't even supposed to be working that day. In fact, he was getting ready to buy a house in Seward and was planning to sign the papers that morning. But another conductor called in sick and Lowe took his place.

Already a railroad man for 17 years, Lowe was switching cars in the Seward train yard, located directly on the waterfront, when the earthquake struck on March 27, 1964. "He told me he looked out the window of the caboose and all he could think of was the Bible - the Red Sea parting" recalled Lowe's wife, Shirley. The bay emptied within minutes after the earthquake.

A Navy veteran, Lowe knew when the ocean pulled back like a curtain from the shore that something was going to happen. Later, Lowe would joke to friends that he was the only man living who had ever seen the bottom of Resurrection Bay. But he wasn't laughing as the wall of water, towering 20 or 30 feet in the air, hung motionless overhead just before the tsunami struck.

Lowe jumped off the train that moments later would be washed out to sea and started running like hell, laughed Shirley. Past the tank farms toward the mountains. At 6 feet 4 inches and 220 pounds, Lowe still had the physique of the football player he used to be and his long, lanky legs moved like pistons as he raced for his life.

Suddenly, an oil tank exploded and the ground directly in front of him cracked open, dirty, muddy water gushing out of the yawning chasm at his feet. He leapt with only one thought pushing him across the gap. "He decided if he was going to drown, he was going to drown in clean water," his wife said.

The driver of the last car heading out of Seward that day saw Lowe heading toward him and waited. After a quarter mile sprint that probably set a speed record ("When you have all that encouragement behind you, you can move right along," said Shirley.) Lowe was safe, but he was unable to contact his family for three days.

Visiting relatives in New York, Shirley heard from her brother that the Seward train and the entire railroad crew were gone, but she refused to believe her husband was dead. "I just knew that if anything happened to Ralph, I'd feel it. We were close."

Two days later, she was watching a national news program which featured an aerial shot of "two men walking along inspecting a track," she said. "I recognized him immediately."

The next day she got his letter. "We had a little shake, but I'm all right," wrote Lowe.

During 32 years with the Alaska Railroad, Ralph Lowe enjoyed a life full of adventures, although most were not as exciting as the Good Friday earthquake. Ralph Lowe died in a car accident last summer, and on May 4, his portrait was unveiled during a memorial service at the Museum of Alaska Transportation and Industry.

"This is a portrait of a railroader," said board member and full time volunteer Pat Duran before cutting the cake with a toy train on top. "All of the equipment you see here at the museum is only significant because of the people who operated them. All of these people made significant contributions to Alaska in their everyday occupations."

The painting, by local artist Sandra Petal, depicts Lowe, blue eyes scanning the horizon, in his blue railroad jacket "which he wore almost constantly"' said Shirley. "To me, it captures his essence beautifully."

The portrait had originally been commissioned as a present for Lowe's son Barry by his wife Betty. Barry decided to donate the picture to the transportation museum "to share it with everybody."

Those who knew him agreed that Ralph Lowe was one in a million. Always an optimist said his friend Eric Brown. "Ask him how the weather was and he never had a bad word to say. He'd be standing on the dock in Whittier in a pouring down rain with the wind blowing 69 miles per hour. "Just fine," he'd say. "It's a beautiful day."

In 1952 fresh out of the U.S. Navy, Lowe packed up his few belongings in "a little old second-hand car held together by baling wire," said Shirley and left his native New York for Alaska. He arrived in Anchorage practically broke and spent his first night camping out on Fireweed Lane, back then, "a dirt road at the end of the city," according to Shirley.

The next morning, he went down to the railroad offices and hired on as a section hand, commonly referred to as a "gandy dancer." Section hands repaired the tracks with a pick ax and shovel, tamping down ties and putting in new rails by pounding spikes with heavy sledge- hammers. "It was hard work," said Albert Bailey, who worked with Lowe in Whittier, "one of the hardest jobs pertaining to the railroad."

After that first summer, Lowe returned to New York for two years before Alaska called him back. This time, he hired on as a brakeman with the railroad, definitely a step up from section hand. "You needed a few smarts to do that," said Shirley.

Home on leave, he met Shirley through his cousin who was married to her best friend. Within three weeks, they decided to get married. The following spring, Shirley, with her 4-year-old son Barry, drove up the Alcan with another couple in a Pontiac sedan. "The road was terrible. At one point, the ruts were so deep, you couldn't steer the car and the mud was up to the middle of the hub caps." Once, the car had to be pulled out of a pothole by a DC-8 -cat.

At first, the couple moved to Fairbanks, where they lived for four years. Lowe adopted Barry, whose father had died when he was eight months old. "Ralph was his dad," said Shirley. Since Lowe had little seniority, he worked the "extra board," which meant he was frequently dispatched to sites far from his home.

Over the years, the Lowes lived in several small communities along the tracks, Healy, Ferry and Whittier, and had five more children, two boys and three girls. After the earthquake, Lowe was sent to Whittier because Seward was closed. The entire town lived in one building, at the time called the Hodge Building, now Begich Towers. There were about 200 railroad people in the town, and said Shirley, "it felt like a great big extended family."

By then, Lowe had been promoted to conductor and later became dock superintendent and finally trainmaster. "They kind of ride herd on all of the brakemen and conductors," explained Lowe's friend Bailey. "They keep the trains moving."

In 1966, the Lowes bought a home in Anchorage where Shirley still lives and Lowe continued to work in Whittier for 15, years, a week on, a week off, until he retired in 1989. Lowe was responsible for unloading rail barges towed in by tug boat to the Whittier dock. The job was tricky, said Bailey, because you had to backload the empty cars before unloading all the cargo. Otherwise, the uneven weight could capsize the barge. "It was no quick job, six or seven hours" Bailey estimated, to fully unload one barge, no matter what the weather. And the weather in Whittier was mostly terrible.

But Lowe loved the railroad, said Shirley.

"Initially it was because he had a large family and the railroad provided a good job and security."

Eventually however, "the lure, the romance, the excitement, the movement, the camaraderie, all the things that go with railroading, hooked him. He'd take any job where you could hear a train whistle, he didn't care what it was."

Neither 60 below temperatures, moose on the tracks or bears in the garbage can lessened Lowe's enthusiasm for railroading in Alaska. "All in all this, the farthest north railroad in North America, is one of the most fascinating in the world," wrote Lowe in his Journal. "Like the first rails that pushed westward in the early years of our country - this railroad is opening up a frontier, the Last Frontier."

Among railroaders, said Shirley, Lowe was known as the "grand man" because he was always helping people. Lowe died like he lived, shielding his 8-year-old grandson from the impact of the car crash. The boy survived.

"He was willing to do whatever he could and would consistently go out of his way to help people," said Shirley. "Nothing spectacular, just a superbly decent man."

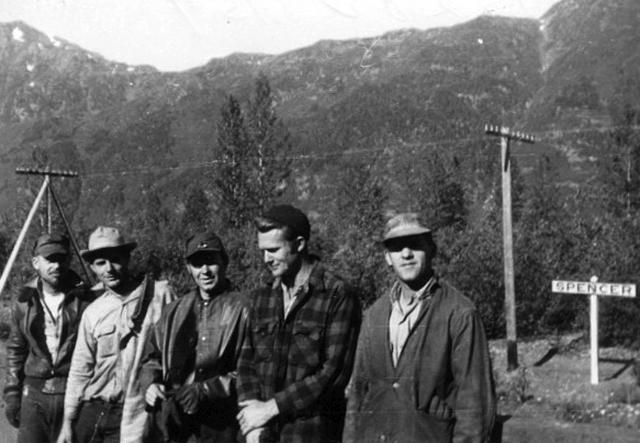

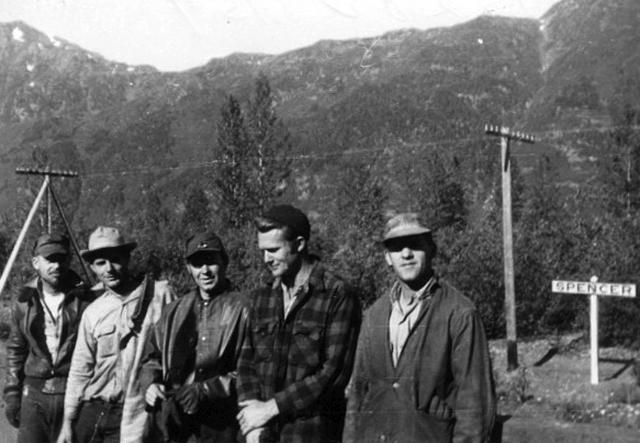

From Valorie Booyer September 4, 2008: I justed stumbled on your website for the first time today, I wish I had done so along time ago, it is fantastic. My father was Ralph Lowe. I noticed you have the article on your website, "Portrait of a Railroader" he held #1 seniority position in the transportation department when he retired as the Trainmaster in 1989 and even then he did not want to retire. The railroad was his life and therefore our life. I often tell people my favorite smell is creasote and the ocean air in Whittier. [This photo is of] Gandydancers/track labor in the early 50's, Healy area I suspect. My father is 2nd from the right, I am not sure who the others are."

© 1996 Northern Mirror